Nature’s way is to provide. It is to protect, to nurture, to replenish. It is consistent, cyclical; it is designed to work by healthy give and take.

A poignant inspiration for artists for centuries, the natural world is breathtakingly beautiful; a beauty created by both its complexities and simplicities.

This online exhibition explores the connection artists’ have with landscapes, animals and natural formations. Through the visual and written work of 20 artists, it seeks to understand a fresh perspective on the desperate need to restore a healthy relationship between human kind and its home.

‘As we move irrevocably through the charnel ground of the world we once knew and relied upon, I walk. Short walks, long walks, walking as creative practice. Movement that is innate, ancient, and much forgotten. As I walk, sometimes shod, sometimes skin to skin with the earth, through mud, leaf litter, the entangled network of tree roots and networks that weave their way beneath the surface, the illusion of self, shaken loose by rhythmic archaic patterns of movement, undergoes a dissolution. New iterations of seeing and listening emerge; the sensing of complex layers of psychic topography, inner and outer. Beauty and pain, light and dark, repulsion and rapture, all intertwined. It is an acute way of listening to place, of receiving information about the complex patterning of the visible and invisible, the tangible and intangible.’

The seemingly sporadic, yet driven textural gestures in Pinilla’s paintings provide a movement that suggests the natural flow of water on Earth. It speaks to a calmness that we feel when experiencing the simple pleasures of the landscape.

Colour is prevelant in both Pinilla and Kraft’s paintings. They emulate those colour’s in nature that you just can’t help to marvel at; those found in sublime sunsets and the centre of geodes. Those colours that are found in nature but somehow do not seem natural.

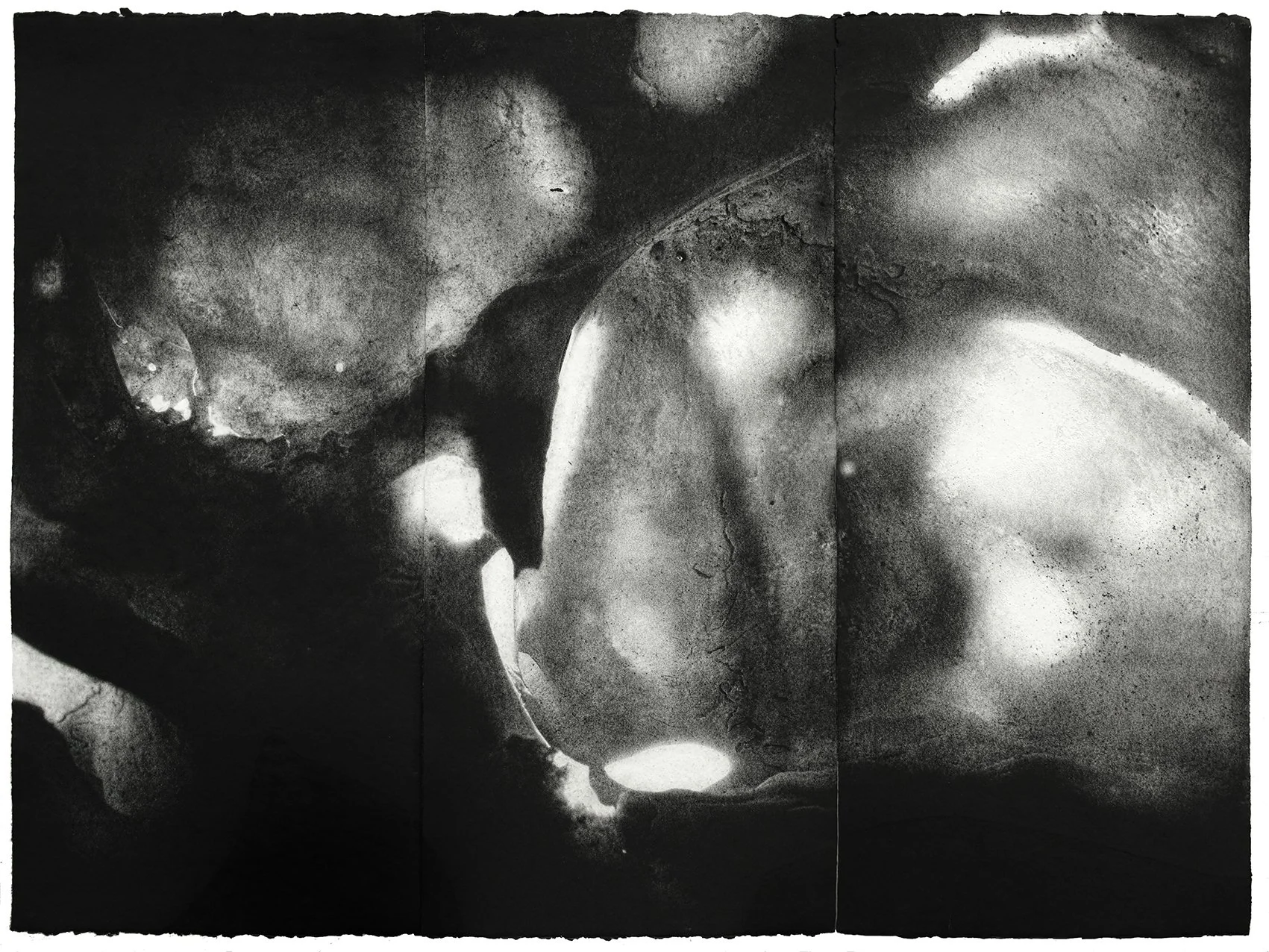

Kraft’s iridescent pigments are balanced by the sharp form of the rocks she depicts. The following paintings show a tougher side to our landscape through the hardy, rocky formations we find on Earth.

Through this body of work, we are provoked to ask questions. What is in between these rocks? How long have they been there? What have they been through?

They almost seem like they have secrets, as if they have lived a long life, evolving in their shape through erosion.

‘As with the nature of handwriting, presenting an array of marks and gestures applied on a particular surface, there is a proximity between the altered surface and the mark-maker.’

Joseph Norris,

The nature of place, as I viscerally learnt during an unforgettable field trip to the Peak District at the age of seventeen, does not make itself known to us only through maps, diagrams, topography, recorded history and archaeology, but also through the permeable animal body of our skin and energetic sensing as we move in repetitive steps in a receptive state, walking off our separation to become that porous and integrated subtle receiver of information and experience - falling into an archaic and regenerative reciprocity. We become receivers of residues, interpreters of subtlety, listeners to voices which exist outside the illusion of linear time and the confines of consensus reality.

There is a consideration to be made about the feeling of awe when we discuss the natural world.

Whilst our understanding of it may be different, the feeling of overwhelming curiosity and reverance is felt as strongly, maybe even more so, to the phenomena existing above us as it is to that of the tangible wonders of the Earth we live on.

Over the years, artists have told the stories of admiration and intimidation assosicated with ‘the sky’ and that which it encompasses.

Through the work of Louise Beer, we take a moment to contemplate the fleeting beauty of clouds; allowing ourselves to find peace in their movement.

In contrast, Dionisio observes a more unsettling perspective. Her work questions what is beyond our atmosphere and presents a view that challenges that of excited wonder; exploring a dialogue around the fear of what is unknown.

I'm scared of large planets. Is this normal? Does it have a name?

I get panicked when I see pictures of huge planets. Sometimes pictures like a big moon over the sky gives me perspirations.

There does not appear to be a specific name for your fear, but that does not mean that it is not a real and legitimate fear. We all have fears of something! Trust me!

How is it possible for anyone to be scared of galaxies and planets?

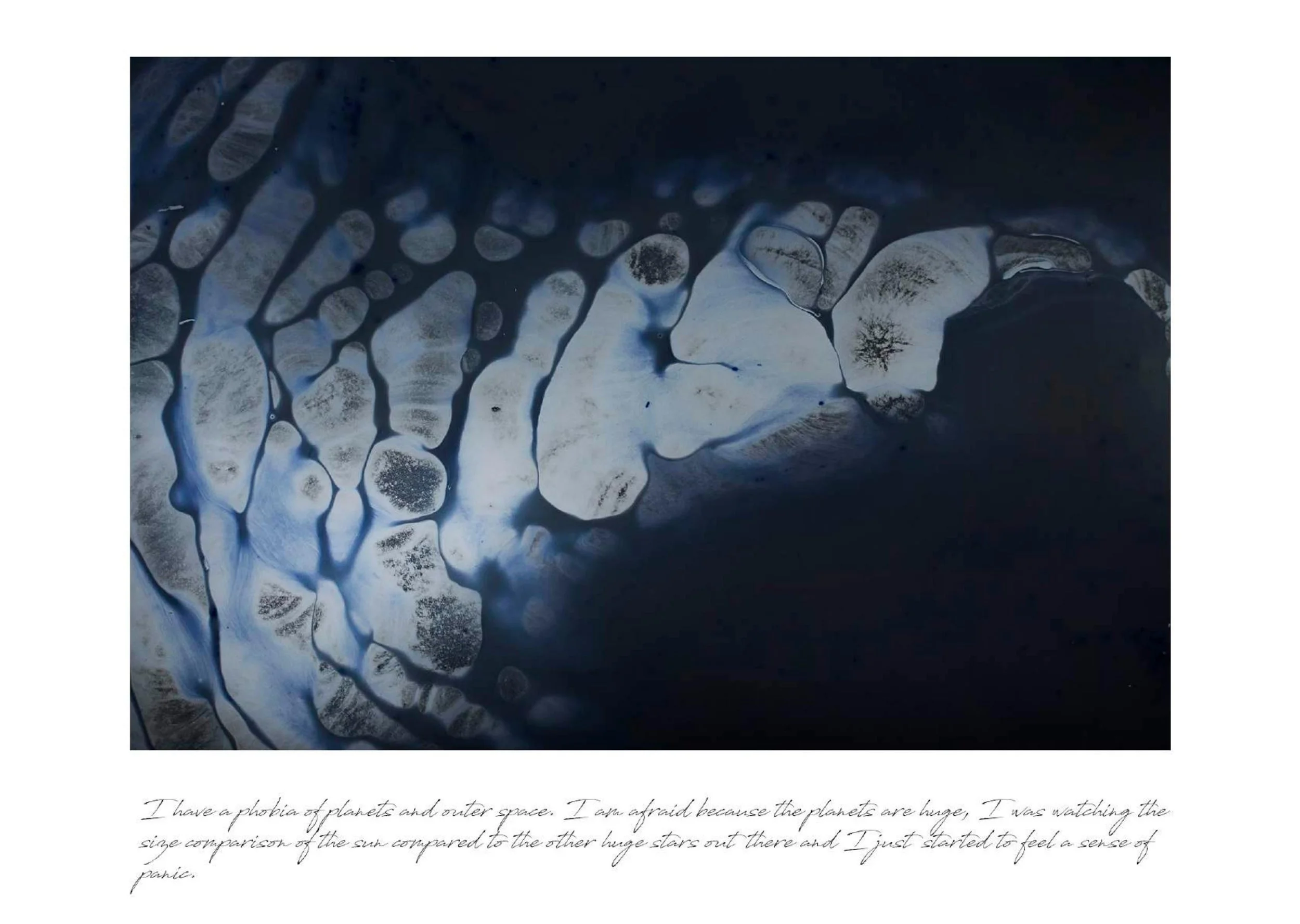

I have a phobia of planets and outer space. I am afraid because the planets are huge, I was watching the size comparison of the sun compared to the other huge stars out there and I just started to feel a sense of panic.

The star comparison charts made me uncomfortable as well...so much that I have to close the book.

It might be a cause of megalophobia: fear of, well, 'big things'. This might include stuff like towers, whales (they scare the crap out of me), other large animals, those kinds of things.

If I am on google maps and I zoom out too much and it shows a huge ocean such as the Pacific ocean, I get queasy and panic big time.

It is even worse if it shows the earth as curved and you can see the deep dark space beyond.

Walking around on this floating mass that is in no way tethered to anything, with no control over anything if you start floating away.

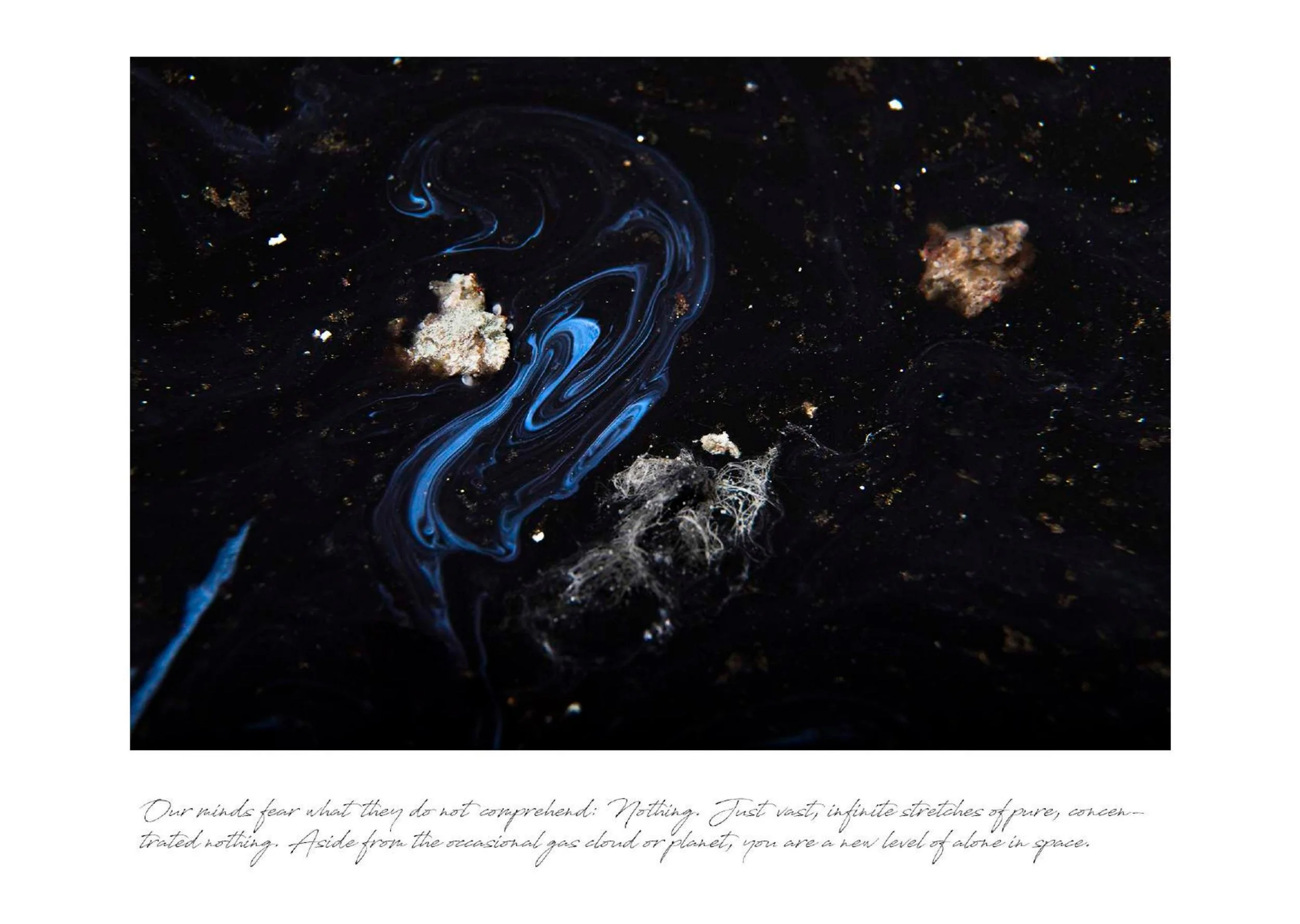

Our minds fear what they do not comprehend: nothing. Just vast, infinite stretches of pure, concentrated nothing. Aside from the occasional gas cloud or planet, you are a new level of alone in space.

Oftentimes you will be the only solid object for several parsecs. There is nobody there and never will be.

There is nobody coming to save you, and nobody will even try. You are the only intelligent being for billions of billions of miles. You will die, terrifyingly alone, afraid beyone measure, and cold.

I have always had this as a kid every time the teacher would tell us how huge the sun was I started overthinking it and started getting sweaty and nervous.

I thought I was the only person on the planet with this phobia. I used to have nightmares about going to space and seeing humongous planets right in front of me and dreams where the moon suddenly filled the sky and I got scared by its size.

It makes me feel like I have travelled so far up the atmosphere that I am in space and no longer bound by the gravity on earth. It feels like I could break off the orbit and float off into space and become nothing.

Whenever I look at photos taken by satellites of multiple planets together, I feel so insignificant, like I do not matter at all in this universe.

We humans can give articulate meaning to the universe in the very act of perceiving and reflecting on it. The amazing thing about the universe is that matter became concious and began trying to understand itself.

My dad used to take me and my sister to look at planets and the moon using a telescope from time to time. The first time I went was when I was 6 years old and just couldn't look.

When I look into space or vast oceans, I feel like I am already one step closer to death. It is a glimpse, but an unsettling one.

Our minds fear what they do not comprehend.

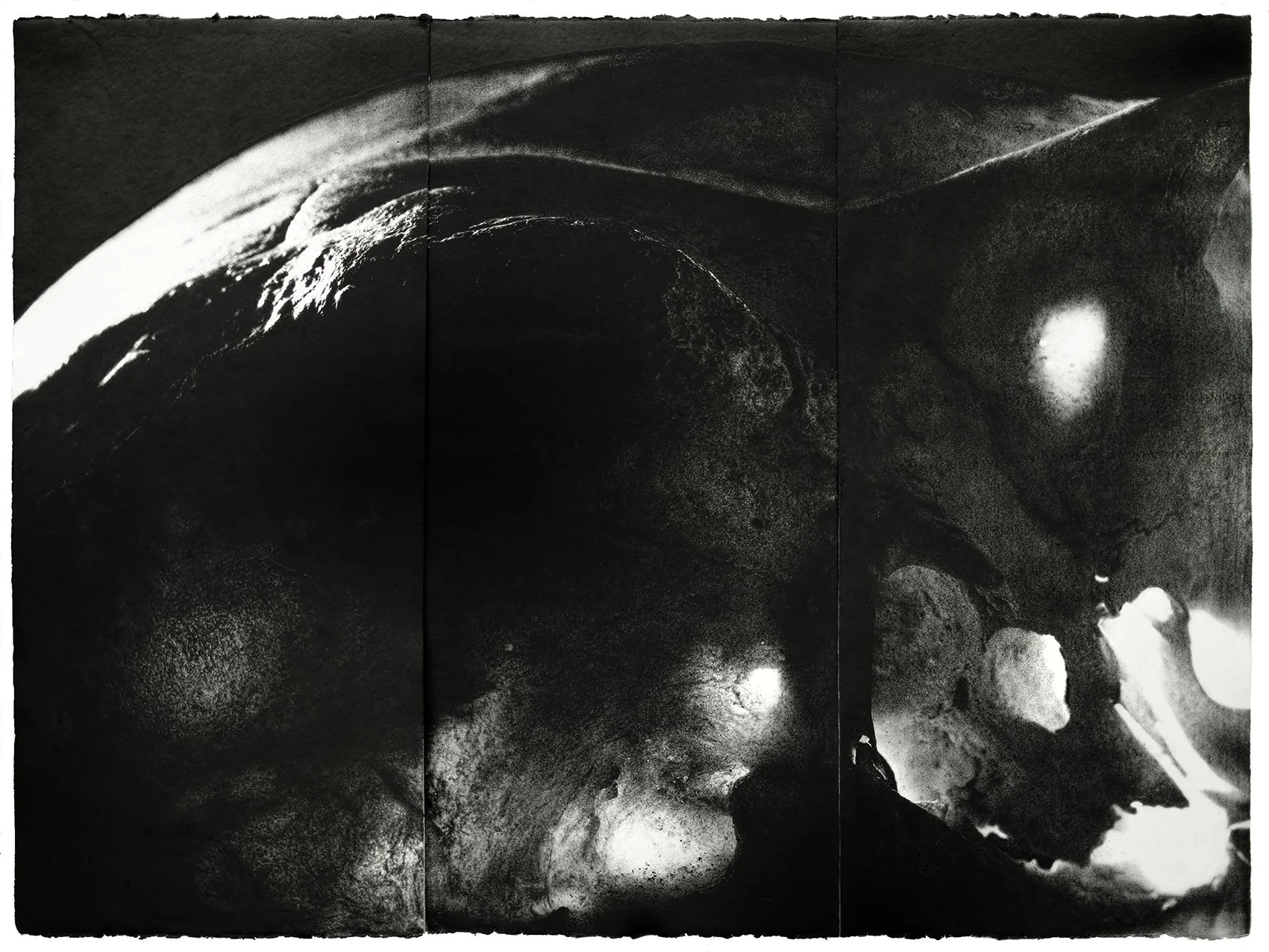

Nourhan Ebrahim’s work showcases the power of photography. Her close up images ensue obscurity into the subject, showing it not as a rocky object, but an entity of texture and intricacies.

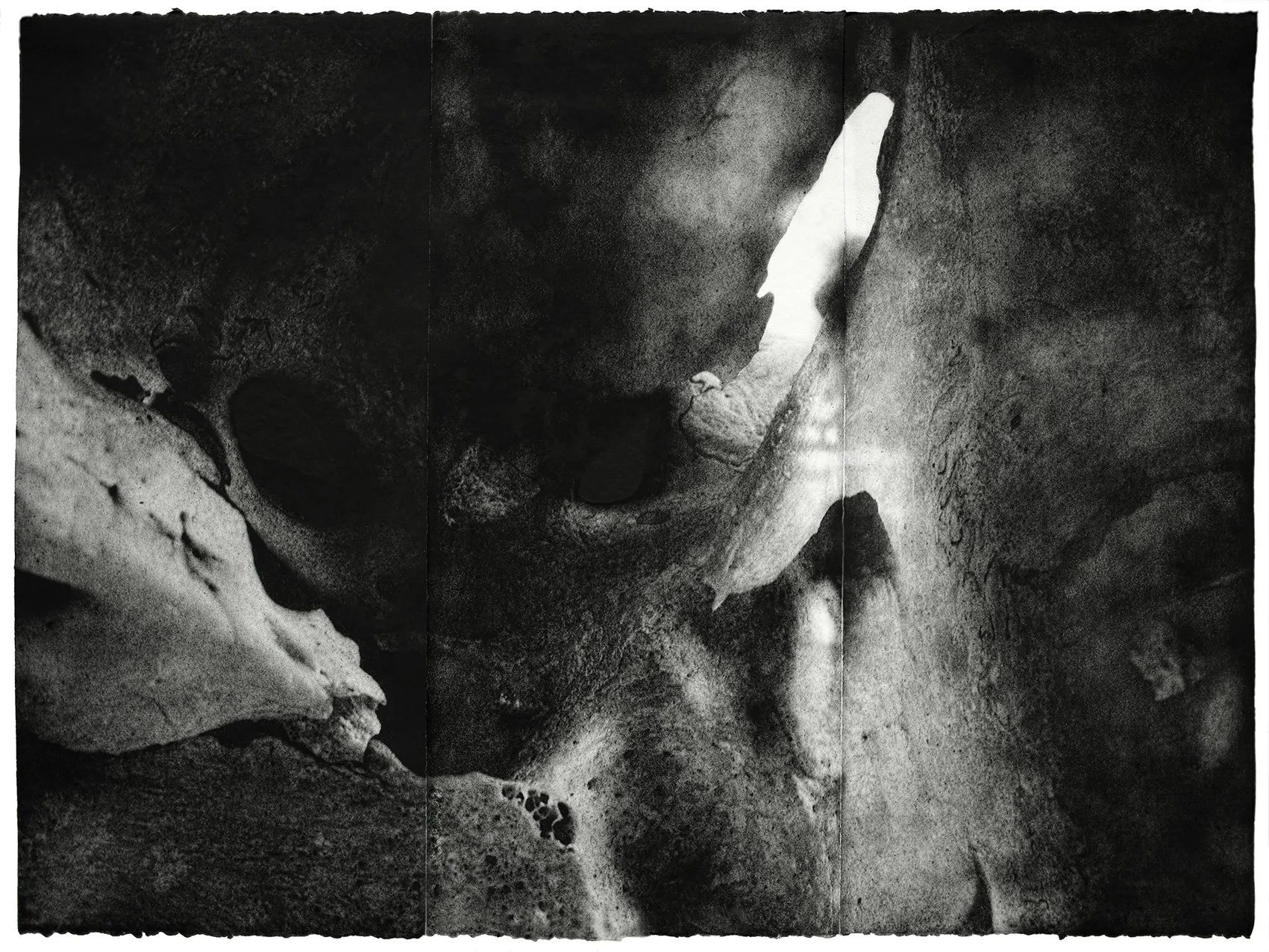

In a similar vein, the work of Carol Wyss ambiguates the subject, depicting the human skull not as we normally understand it, but as a tangled landscape full of winding paths, tunnels and dark caves. The deep tones and illuminating pockets of light make this a fitting, but unique representation of that which encapsulates the human mind.

The final section of this exhibition will discuss the most natural thing of all; death.

The work of three artists conclude our conversation, all exploring the subtle but powerful beauty that can be observed at the end of a life.

Death allows for stillness; for rest. It provides a break in the hustle of life to contemplate that which was once alive. During this contemplation, we should consider the creature’s existence, both physical and philisophical. We should appreciate how the transition to death exposes its other physical forms.

We take this moment to consider how all that dies once was alive; that it served a purpose. Every insect, animal, plant and tiniest of orgnasims play their role in the ever evolving natural world, both in their life and their death.

‘What would it be like to put down the tools of discovery and originality, to forget the pioneering and relentless search for newness in the art world and in personal creative practice, and to rest in a rhythmic, reciprocal, archaic relationship with place; to uncover old ways of seeing and listening that rest the eyes from tired screens and the seclusion of private studio spaces?

What would it be like to walk out into the world to perceive and receive all kin through the porous animal body, the soles of the feet, and with the inner eyes and ears of the heart?

What artworks, or vessels for listening would emerge from that kind of engagement?’

Louisa Chase,